Night in the Woods is a game about love, pain, and the dire need to break things. It’s about human experiences and the inhuman conditions people force upon each other. It’s about resilience, anarchy, and stealing pretzels to feed a colony of rats so that one day they can own Possum Springs. Night in the Woods is about the things people say, and more importantly, the things they don’t.

Let’s back up a step. There’s a lot that I’m predisposed to liking about Night in the Woods: The game’s developer, Infinite Fall, was founded as a worker co-op. The game itself sets out to explore the culture, mythology, and trappings of American midwestern boomtowns–a setting that’s underrepresented in modern media. And its plot is secondary to character development, so the game can afford to take its time with small scenes.

Even still, when I first started playing, I wasn’t sure what to expect. The game throws you into a brief poem-history where your character–Mae Borowski–reflects on grandfather passing away before she left for college.

I really like how this is presented, even though it doesn’t quite gel with how the rest of the game’s story is told. You have a few choices to make in this poem, from an important historical event that Mae recalls from the town’s recent history to Mae’s grandfather’s dying words. As far as I can tell, these choices have no effect on gameplay or future story; it’s a minimal info-dump that you get to participate in. But it’s a well disguised info-dump.

After that, we jump to the present day. Mae is 20 now, but she’s not a college student anymore. She doesn’t want to talk about it. You come in at the train station late at night, make your way home, and get to reconnecting with your friends in Possum Springs.

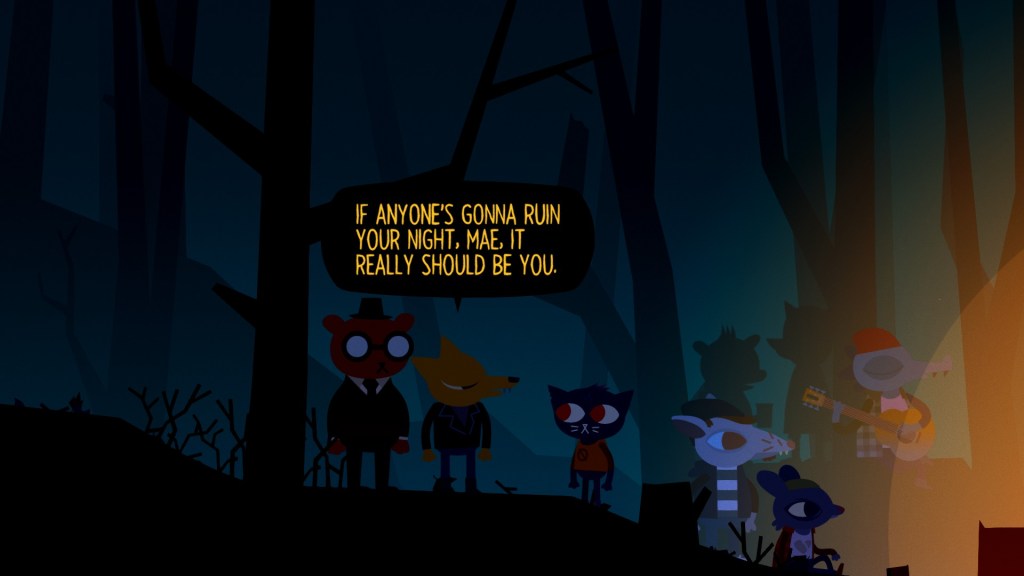

Once you’re into the thick of things, the flow of dialogue really starts to stand out. A lot of the game’s conversations are short, and have this kind of quirky, quippy humor to them. There’s a lot of attention given to how text appears on screen, too. Everything’s written based on how it looks in speech bubbles.

It’s like the start of a new paragraph.

It catches your eye.

It’s punchy.

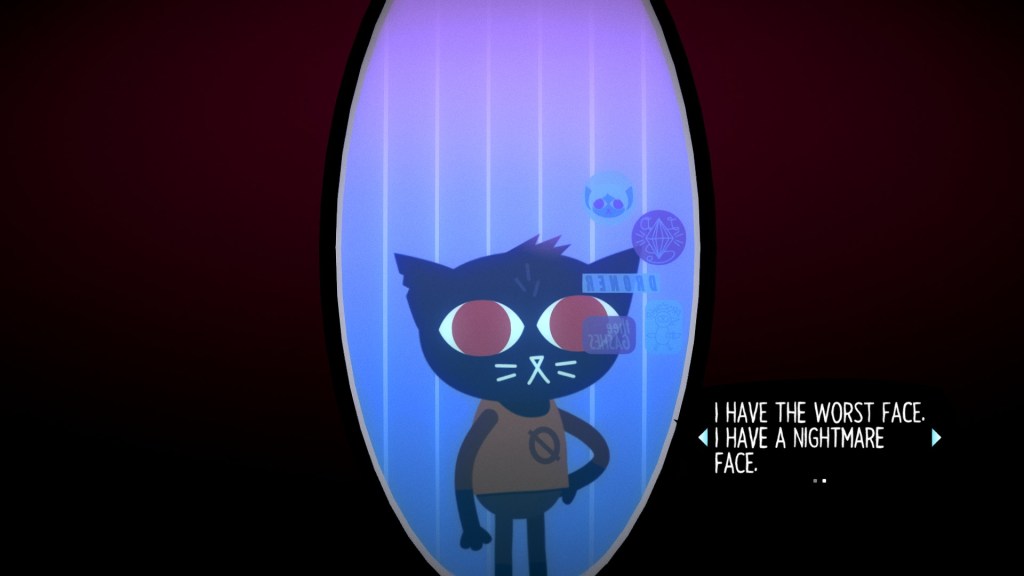

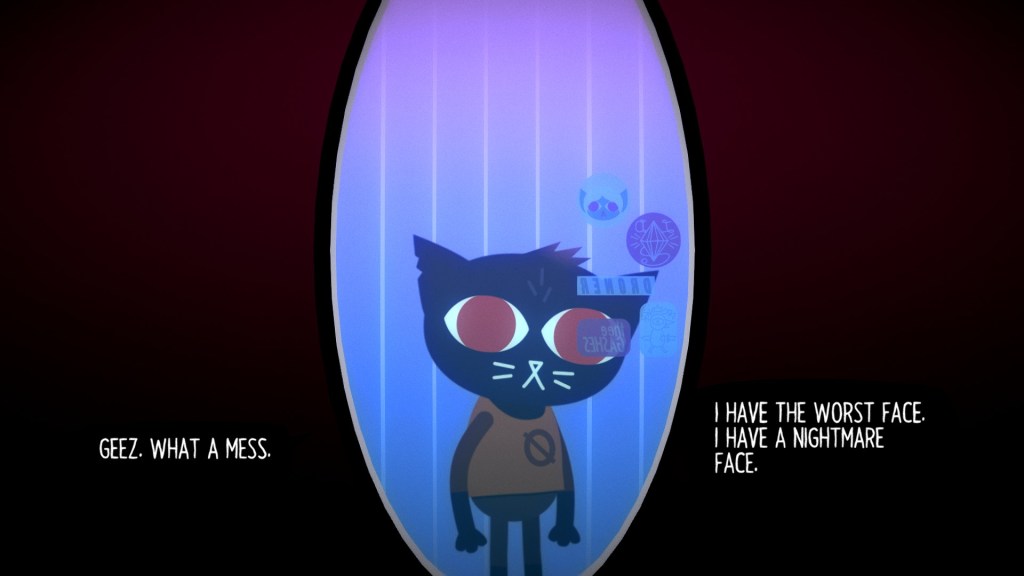

And, importantly, things like text color and location communicate who (or what) is speaking. At first this might seem like a pretty small detail, but it allows for some really interesting screen perspectives while you’re hanging out with your group of friends. It also helps enhance the scene that really drew me into the game: Mae prepping for a party at the mirror.

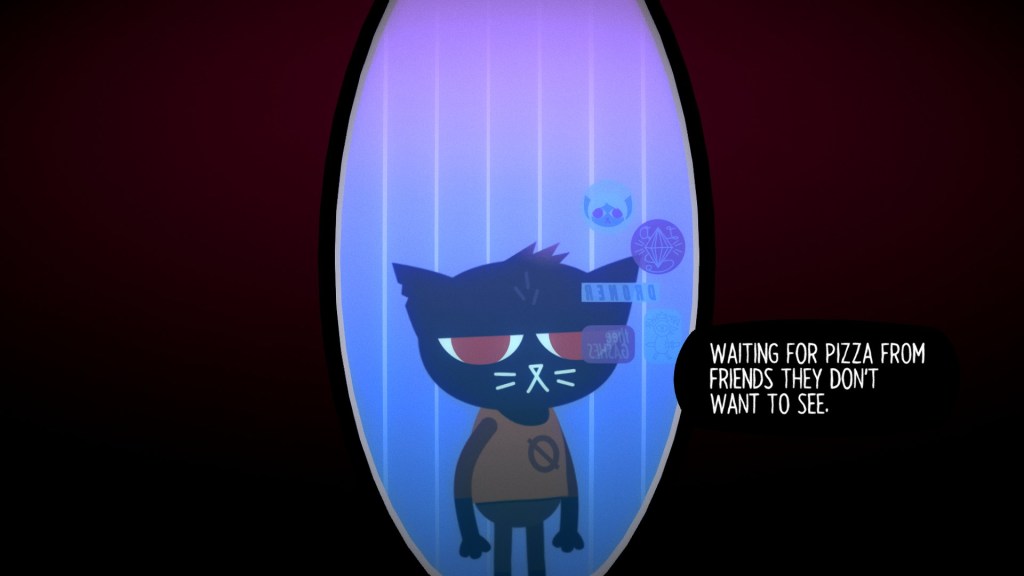

The mirror is Mae’s first real monologue. Prior to that, the only time you read her mind is when she’s examining something in the town around her. Here, it’s just Mae. And you. The dialogue flips back and forth from the left and right sides of the screen as you direct her anxious thoughts. And there’s a lot to love about it.

I especially like the jump to thinking about Cole–Mae’s high school romance. It’s a stark non-sequitur. One moment she’s talking about wanting to be liked while hating everyone else and then it hits.

Mae doesn’t want to be a hermit. She doesn’t hate everyone–she hates not feeling loved. And right here, Cole is the face of that issue.

Non-sequiturs are a tool Interactive Falls seems fond of. They’re a great way to jump between points or build tension in a conversation. But here, in this specific case, it’s a way to highlight what seems like the underlying issue faces Mae with party.

A lot of RPGs suffer when dealing with degrees of separation between the player and their character. Generally, the more choices a player has in the course of events, the more of a self-insert their character is, and thus the less personality they have. Commander Shepard is exactly *nobody’s* favorite character in Mass Effect, for instance, because they have the personality of a wet paper towel–they conform to whatever surface you throw them at, and they fall apart on any real inspection. That’s because Mass Effect expects you to fill in the details–which alien crewmate does Commander Shepard get to bone? Is Shepard a saint or a genocidal maniac? There isn’t room for Commander Shepard to have explicit preferences, a consistent personality, or even short term memory.

Not so with Mae Borowski.

Night in the Woods, with its much tighter scope, has a pretty elegant solution to this issue. Any choice you make is something Mae would do. You don’t decide *whether* Mae has a dark secret, or even when she chooses to confront it. You decide how she avoids talking about it. The only choices you make that majorly impact the story have to do with which side adventures you go on or who you want to hang out with each day. Once you’re there, it’s another well contained mini-adventure.

This leads to a really interesting style of player engagement. Sometimes you pick a dialogue option because you want to hear what it reveals about Mae–not because it’s what you would say. You’re no longer ascribing character to someone, but discovering it. It’s like a more active form of watching a movie.

There’s also one other piece of fallout from this that I’ll be returning to because it’s crucial to some of Mae’s relationships and her personal story. Mae’s ignorance is our ignorance. Whether she does not know or has actively avoided confronting something, we’re left to wonder.

With that in mind, I want to look at Mae’s group of friends.

Gregg

Gregg’s a blast. He and Mae make for a lot of comic relief riffing off each other, even as you flee from the scene of your crimes or (possibly) electrocute Mae to death. Their tone together is pretty well set from the moment you first see him at the Snack Falcon.

Gregg fits pretty neatly into the dumb idiot friend category, but he has a lot going on, narratively. He mirrors many of Mae’s anarchist ideas, and the two can spend a lot of time together getting up to petty crime. On the surface, their relationship is built on catharsis. It’s about breaking things and being a rebel for rebellion’s sake.

But that’s just the surface.

Not every day is an “upper” for Gregg. And he sometimes makes a point of saying as much. On the day Angus fixes Mae’s laptop, Gregg drops his first hint that all isn’t well.

Gregg: “I’ve got dinner with the family.”

Mae: “Is that a good thing or a bad thing?”

Gregg: “A friendly thing.”

This kind of understatement permeates a lot of the dialogue in Night in the Woods. It’s a non-answer that paints enough of a picture for you to assume an answer. And in Gregg’s case, as you get to know him better, you learn about his troubled childhood and the physical abuse he faced from his uncle.

Gregg and Mae don’t just get along because they’re rebels–they get along because they’re both outcasts, not necessarily from their families, but from the town. There are people in Possum Springs who will never take the time to understand either of them. But they understand each other.

Angus

“It’s not magic.

We’re just atoms.

And our perception of reality is just chemical reactions.

Take those away and poof, there goes the universe.”

Angus gets the least screen time out of Mae’s friends. He can even end up with less 1-on-1 time than certain side characters, depending on your choices. But he plays an interesting role as both a partner and a foil to Gregg, and also a foil to Mae.

If I were to scrunch Angus’ personality up into a few sentences, I’d say that he’s generally level-headed and rational, sometimes to a fault. He’s sympathetic towards Mae and other characters, even if they’re a little too emotionally or spiritually guided for his taste.

This is most evident when Mae leads the group to try to solve the kidnapping from Harfest. Angus sincerely believes that Mae witnessed *something* that night, but isn’t keen on Mae’s insistence that the perpetrator was a ghost. If you choose to investigate Possum Jump together with Angus, you get some pretty heavy reveals about his abusive family members, childhood trauma, and the roots of his skepticism. You’ll also flee from a cultist together, only for Angus to backtrack and claim that the individual you saw was probably a maintenance worker.

He’s afraid to be afraid, even more than he’s afraid to be wrong.

Bea

Bea isn’t the most exciting party member, but she’s the one friend of Mae’s that interests me the most. Unlike Gregg and Angus, Bea really doesn’t *like* Mae. In fact, some of Bea’s actions really make it seem like she wants to hate Mae, but can’t bring herself to. She’s a sympathetic character. She begs to be helped, but neither you nor Mae have the means to change her life the way she needs.

Bea’s relationship with Mae is a kind of found family story, but Mae, through her lack of understanding, keeps stepping on Bea’s toes when she’s hiding from her problems. This kicks off almost as soon as we meet Bea–Mae questions Bea ‘playing’ drums in their band using a laptop. Mae then goes on to prod Bea about working at her family business, not knowing that Bea’s mother died while the two were still in high school. And she doesn’t know that Bea has been longing to escape to college, but can’t because of her obligations to her father. Mae had everything Bea wanted, and to Bea’s eyes, Mae threw it away.

And we participated. Again, Mae’s ignorance is our ignorance. And that’s powerful.

I generally wouldn’t be concerned with spoilers in an essay like this, but there’s one scene I insist anyone interested in the game check out for themselves. After Harfest and after the group manages the investigations looking for Mae’s ghost, you’re asked to hang out with whichever party member you spent the most time with once more. If that’s Bea, she takes you to a college town where you go to a party together.

It’s a beautiful exploration of friendship in the face of failure, and what it means to be there for someone.

The End (Here there be spoilers)

Neither Night in the Woods nor its characters are afraid to engage in politics; while our protagonist, Mae, might be an anti-capitalist, anti-fascist anarchist, the game’s overarching narrative draws a much clearer connection between capitalism’s boom-and-bust nature and the rise of fascism than Mae ever could. In Possum Springs’ supposed former glory, the town’s fascist cult finds inspiration. In the town’s crippling decline, which was brought on by a lack of resources and an inability to compete with emerging markets in tech and business, they find a hatred for the outside world.

It’s not an accident that their god–the Black Goat–is made manifest in a hole in the town’s mine that likely swallowed countless innocent workers in the name of profit. And rather than seeing it as a monster, they have come to feed it.

The cult appears to meet its end when Mae, who has experienced and rejected the Black Goat, together with Gregg, Angus, and Bea, traps the cultists underground.

The group then returns to town, and you as a player have an opportunity to reflect on Mae’s experiences there, including the individuals she has affected.

I think a lot of people might see the end of Night in the Woods as lacking solutions. Mae, though safe, is still stuck in an ever-changing Possum Springs that her friends plan on one day leaving. Bea still has to run her shop while her father sucks up the value of her work and wastes away depressively. The cult, though buried, is not confirmed to be gone. And though the town is brighter, it will never be at the top of the world.

And I think that’s the point. The game’s end is optimistic, not because it’s given players an answer, but because it’s given them tools to find their own. You can find peace in change. You can value yourself separately from your work. You can form and live in a community while keeping your arms open to those in need. You don’t have to succumb. And your friends, through proximity or a shared love for petty crimes, will be there with you.

It’s a game about love, pain, and the dire need to break things.

Leave a comment